Yes, indeed! This is one of the most important and vital skill development, that many reading programs miss out on. And over 10 years of working with children, I have realised that a lot of children who struggle with reading have this skill never really worked upon.

The Foundation For Reading And Spelling Success – Developing Phonemic Awareness

For many years, phonemic awareness has been recognised as one of the most reliable building blocks for – and predictors of – success in reading and spelling. Despite this, many children never receive sufficient high-quality, explicit instruction in phonemic awareness skills to make optimal progress in literacy. This guided e-book will try to answer some important questions:

- What is involved in teaching phonemic awareness and for how long should it be taught?

- What is the relationship between phonemic awareness skills and phonics skills?

- How can you develop them by incorporating proven strategies in your daily practice?

For many years, phonemic awareness has been recognised as one of the most reliable building blocks for – and predictors of – success in reading and spelling. Despite this, many children never receive sufficient high-quality, explicit instruction in phonemic awareness skills to make optimal progress in literacy. This guided e-book will try to answer some important questions:

What is Phonemic Awareness?

Phonemic awareness is a subcategory of phonological awareness. It is the conscious awareness of phonemes, the smallest units of sound in a spoken word.

Changing a phoneme in a word changes the word’s meaning. For example, changing the phoneme /o/ in the word ‘mop’ to the phoneme /a/ changes the word ‘mop’ to ‘map’.

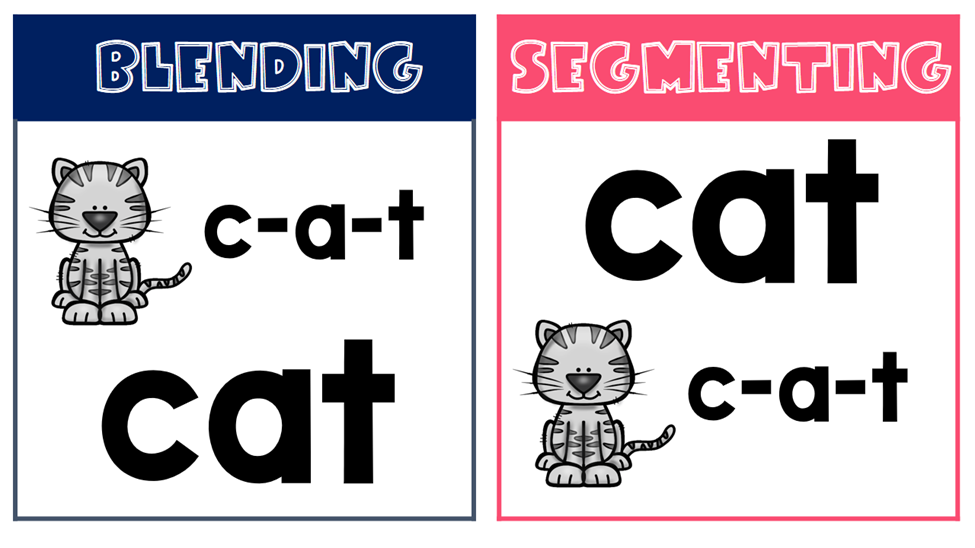

Two of the most important phonemic awareness skills for literacy development are Blending (joining speech sounds together to make a word) and Segmenting(breaking a word into its component speech sounds).

Phonemic awareness is the foundation for reading and writing English (and other alphabetic languages) because an alphabetic orthography/spelling system maps print to speech at the level of the phoneme. Consequently, according to cognitive scientist Dr Keith Stanovich:

“Students who cannot hear, and work with the phonemes of spoken words will have difficulty learning how to relate these phonemes to letters when they see them in written words.”

From a very early age, children recognise the phonemes of the language spoken in the home (as opposed to those of other languages). However, research suggests that most children do not first enter school skilled in phonemic awareness. They are meaning-focused and do not think about spoken words as strings of phonemes. The neural pathways of the brain need to be programmed to attend to the ‘bits’ of words. Research also suggests that if there is no explicit instruction in phonemic awareness, many will fail to acquire it.

What is involved in teaching Phonemic Awareness?

Phonemic awareness instruction should be deliberate and purposeful, not merely incidental ‘play with sounds’. An effective Phonemic Awareness approach explicitly teaches children to recognise, understand, and manipulate sounds in their spoken language. It addresses six phonemic awareness skills:

- Isolation: The child recognises individual sounds in a word, e.g. /t/ + /a/ + /p/ = ‘tap’ begins with /t/. It ends with /p/

- Matching: The child recognizes thecommon sound in the 3 words, /t/ + /a/ + /p/ = ‘tap’, /t/ + /o/ + /m/ = ‘tom’ and /t/ + /u/ + /b/ = ‘tub’. The common sound is /t/.

- Blending: The child listens to a sequence of separately spoken sounds and they combine the sounds to form a word, e.g. /t/ +/a/ + /p/ = ‘tap’

- Segmentation: The child breaks a word into separate sounds and count how many sounds they hear, e.g. ‘tap’ = /t/ + /a/ + /p/ = 3 sounds

- Deletion: The child removes a phoneme from a word to create a new word, e.g. bat – at (deleting the first phoneme /b/)

- Addition: The child makes a new word by adding a phoneme to an existing word, e.g. at – bat (adding a phoneme /b/ at the beginning)

- Substitution: The child substitutes one phoneme for another to make a new word, e.g. bat – mat (replacing the first phoneme /b/ with /m/)

Please Note: These 7 activities mentioned above are to be practiced with your child ORALLY ONLY!

Systematic phonemic awareness instruction will begin with 2-phoneme words, move on to 3-phoneme words, and when the child has mastered these, continue on to 4-phoneme words, and so on. It is hard for young children to isolate the component sounds of blends (such as ‘tr’ and ‘str’), and to segment and manipulate those components. Children should be given sufficient direction and practice to achieve automaticity.

Phonemic awareness tasks involve listening and speaking. They do not involve letters.

Some children may need instruction in awareness of mouth movements or training in cued speech in order to be able to isolate and order sounds. The use of phonic whisper phones can make it possible for children to hear the speech sounds created by their own mouth more clearly.

Phonemic awareness (PA) should be a high priority in literacy instruction in the first initial years. PA training approach described in research literature suggests that relatively modest amounts of time allocated to PA instruction can increase phonemic awareness performance (Brady & Moats, 1988; Yopp, 1997). 10-20 minutes of instruction, three to five times per week is typical in this approach. The intensity and duration of phonemic awareness instruction should be individualised, however, as some children will require more PA instruction than others.

Children who are likely to need more intensive PA training, and for longer, than their peers include:

- Dyslexic children who have a phonological deficit.

- Children who have an auditory processing disorder.

- Children whose first language does not contain the same sounds as English.

Because phonemic awareness is the primary pre-requisite for reading and is such a strong indicator of future reading ability, it is vital that PA instruction be provided for as long as a child needs it and target the specific skills the child lacks.

Phonemic awareness tasks can be easily built into any phonics lesson to consolidate and develop PA skills. Children are never too old for these. Here are some teaching ideas:

- Phoneme Blending: Before they can even begin blending and reading actual words, I want to make sure that their ability to blend sounds rally (no print letters involved!) is really solidified. I’ll say the sounds in a word (like /t/ /o/ /p/) and the child has to blend these sounds and blend to say the word (“top”).

Try practicing with and without visuals: Visuals and manipulatives can be a big help for children who are learning to blend. I like to practice both with and without visuals. If a child is really struggling, I might try a few different visuals to figure out what works best! Here are a few examples:

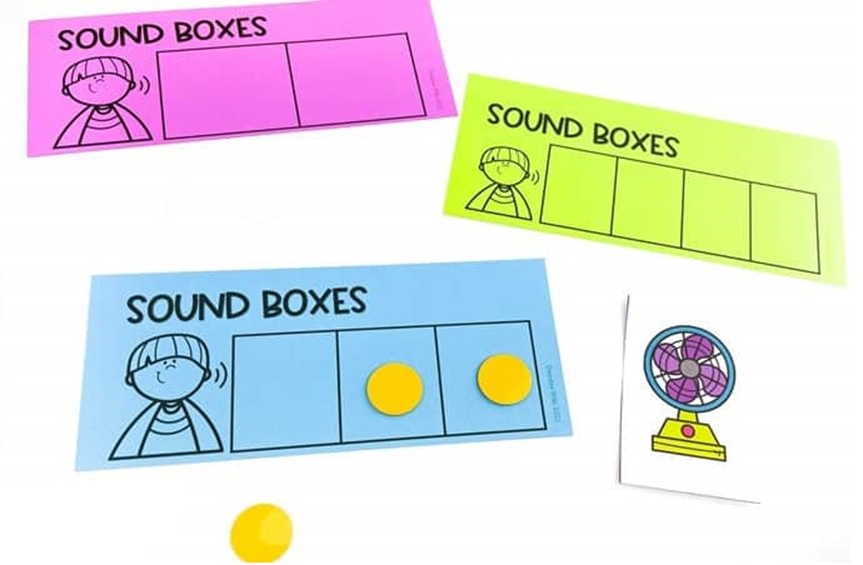

Visual #1 – Elkonin or sound boxes

You may have heard of these before! Children touch each box as they say a sound in a word, and then blend the sounds together. You can also have the child push a counter into each box to blend.

These boxes can also be used to work on segmenting (the opposite of blending).

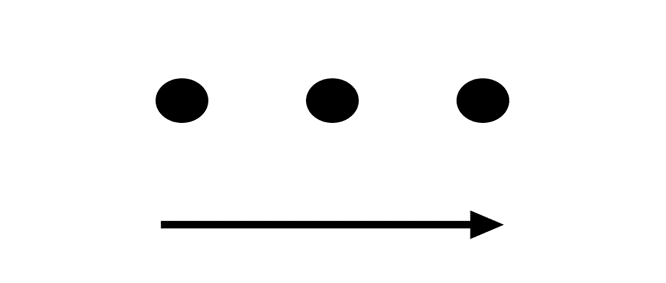

Visual #2 – Dots & arrow

This is one I created to help my daughter. The child touches a dot as they say each sound, and then slide their finger along the arrow to blend.

- Incorporate movement: I’ve learned a few different ways to have children practice blending. The first one is ideal for Kindergarten children (or any child who don’t have great fine motor control yet).

Strategy #1 (great for 3-sound words): Have the child extend one arm. As they say one sound, they touch their shoulder with their other hand. As they say the next sound, they touch their elbow with one hand. As they say the last sound, they touch their wrist.

Like this:

/m/ (touch shoulder)

/u/ (touch elbow)

/g/ (touch wrist)

mug! (say the word)

Strategy #2: Teach your child to blend on the fingers of their non-dominant hand. They touch their thumb to their index finger as they say one sound, their thumb to their middle finger as they say another sound, and their thumb to their ring finger as they say another sound. (You can also involve the pinky for 4-sound words.)

- Leave NO “space” between sounds while practicing oral blending: If a child is having a tough time with blending sounds (orally), leave NO “space” between sounds.

For example, instead of making the sounds in “mat” with choppy blending (having a slight pause after each sound), like this: /m/ – /a/ – /t/, make it sound more like this: “mmmmaaaaat.” (Don’t take a pause between each sound) – Practice Smooth Blending.

Of course, with some sounds (the continuous sounds – a, e, f, i, l, m, n, o, r, s, u, v, z) this is easier to do than others.

Slowly say and blend all sounds without any disconnection between sounds - Start with 2 sounds rather than 3: Parents and teachers tend to jump right to CVC words when having children practice blending. However, whether you’re practicing phonemic awareness or actually reading words, you can always start with 2-sound words and then move towards 3 and 4 sound words, like…

ab

ba

at

in

on

up

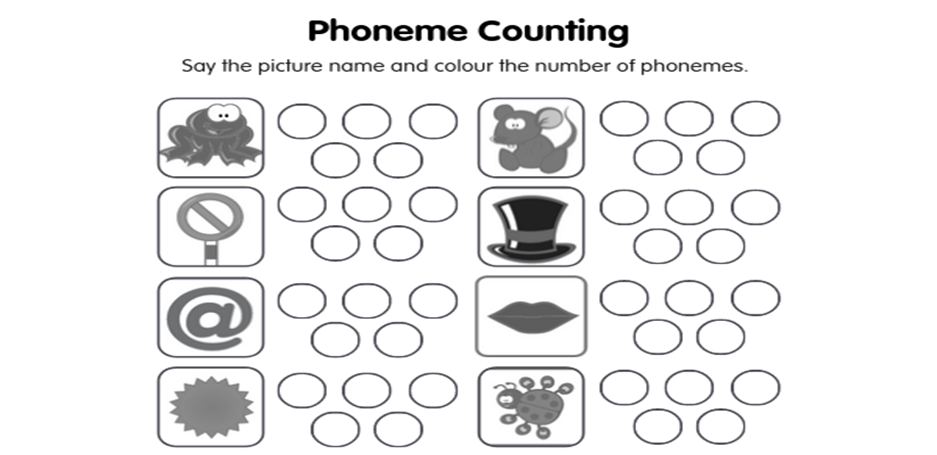

etc. - Phoneme Counting: The child can be asked to sort words according to the number of phonemes they contain (include some consonant blends for a challenge).

- Phoneme Spotter Stories: This require the child to hear through a text, locating and highlighting words that contain a target phoneme. There may be multiple representations of the phoneme in the text. Google ‘phoneme spotter story’ to find plenty of examples.

- Phoneme Substitution: Have your child play a word change (substitution) game in which they must change one phoneme of each word in a chain or word ladder/pyramid, e.g. cup-cap-tap-top-mop-mob-sob.

The amount of emphasis you put on phonemic awareness should reflect a child’s need. Approximately 20% of children will have difficulty developing the ability to ‘listen inside a word’. A key indicator of a child with weak phonemic awareness is the inability to represent each sound in a word with a grapheme in spelling. e.g. ‘stray’ is represented as ‘stay’. This is a different weakness to that shown here:

In this sentence, every phoneme is represented, but sometimes with the incorrect grapheme.

The child with weak phonemic awareness needs help to recognise the sounds in a word. The child with poor knowledge of letter-sound correspondence needs help to master rules that apply to choice of representation of a phoneme.

When you are teaching a child to read, it is tempting to move the child to phonics learning directly without having worked enough to develop their phonemic awareness skills. However, it makes no sense to ask a child who cannot hear the sounds in a word to represent them with letters.

It’s highly advisable to work orally on the above mentioned activities and develop their phonemic awareness skill, before moving to the next level, of making the child read words.